When Mathematics Points Beyond Itself: The Case for an Infinite Ground of Being

Published: October 16, 2025

Why Our Best Equations Point Beyond the Finite

Bridging from the Previous Argument

In our previous piece, we established something that materialism cannot explain on its own terms: the existence of anything at all. By demanding rigorous explanation for every phenomenon within the universe while dismissing the universe’s own existence as a “brute fact,” materialism commits special pleading—applying its core principle everywhere except where it becomes inconvenient.

Following that principle consistently led us to recognize that reality requires a necessary, unconditioned ground of being. Not a contingent universe with specific laws that might have been otherwise, but something whose very nature is to exist—what philosophical traditions have called the ground of being, pure actuality, or being itself.

If you haven’t read that argument, here’s the core insight: existence itself cannot be caused, because causality operates within existence rather than upon it. To ask “what caused existence?” commits a category error, like asking what’s north of the North Pole. The meaningful question isn’t what caused reality, but rather: what is the nature of the foundation that requires no external cause?

We answered: it must be necessary (not contingent), self-explanatory (not dependent on something external), and unconditioned (without limits that would require explanation). Only such a reality could serve as a rational ultimate, avoiding both infinite regress and arbitrary stopping points.

But that raises a natural next question: What can we know about the nature of this necessary ground?

Logic told us it must be unconditioned—without limits, boundaries, or specific determinations that would make it contingent. But there’s another way to approach this same question, one that might surprise you: through mathematics.

Mathematics won’t prove the existence of God—the logical argument already established the necessary ground. And it won’t prove the ground is infinite with deductive certainty. But when we examine the mathematical tools we use to understand reality, something remarkable emerges: a systematic pattern pointing in precisely the same direction as the logic.

What this piece establishes—and what it doesn’t:

This essay makes two distinct arguments:

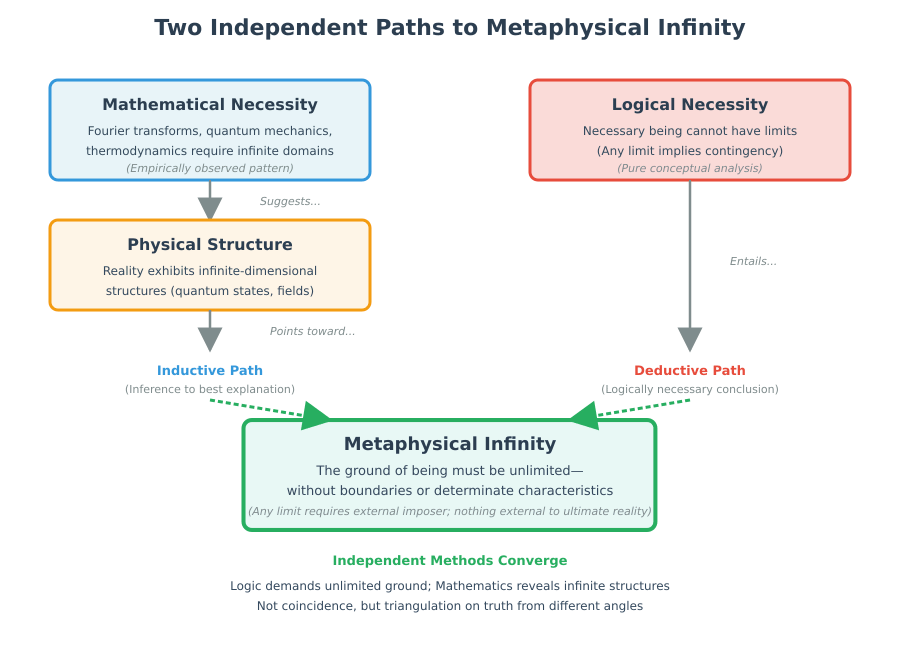

A deductive logical case (presented in Section 7): Any limit on the ground of being would require something external to impose it, but nothing is external to ultimate reality. Therefore, the ground must be unlimited—infinite in the metaphysical sense. This argument stands alone and is logically airtight if you grant the premises.

An inductive case from mathematical physics (Sections 2-6): Our most fundamental descriptions of reality—Fourier transforms, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, field theory—systematically require infinite structures to work correctly. This doesn’t prove metaphysical infinity, but it provides convergent evidence from an entirely different angle.

We’ll present the mathematical pattern first because it’s more accessible and concrete. But readers should know: the logical argument is the foundation. The mathematical evidence is confirmatory support, not the basis of the claim.

The stakes matter beyond abstract philosophy. If the ultimate ground of reality is fundamentally unlimited rather than bounded, this transforms how we understand everything built upon it—including the inexhaustible depth of scientific discovery, the boundless nature of understanding itself, and why reality keeps surprising us with new complexities that our theories must perpetually stretch to accommodate.

The question “is reality’s foundation finite or infinite?” isn’t academic. It’s about whether existence has an ultimate ceiling—some final boundary beyond which nothing more can be—or whether the ground of being is, in its very nature, without limit.

Let me show you why both logic and mathematics point decisively toward the latter. And why this convergence from independent directions creates a case that demands serious consideration.

The Engineering Hint: When Mathematics Demands Infinity

Before we dive into abstract philosophy, let me start with something concrete. You’ve encountered infinity more often than you might think.

Consider π—that endless decimal 3.14159… that continues forever without repeating. We can calculate it using infinite series, adding terms that get progressively smaller but never quite stop. The fascinating part? These infinite sums converge to exact values. The infinity isn’t a bug in our mathematics; it’s how we access precision.

Even simpler: divide 1 by 3 and you get 0.333… repeating forever. We encounter infinity in grade school arithmetic without realizing its significance.

Or look at fractals. A coastline exhibits infinite complexity—zoom in at any scale and you find more detail. The same pattern appears in snowflakes, blood vessels, tree branches. Nature seems to employ infinity as a design principle. These aren’t mathematical curiosities; they’re hints about how reality actually works.

But here’s where my own journey into this question began—not in philosophy but in late-night problem sets.

I remember hunching over my engineering textbooks, coffee going cold, staring at Fourier transform equations. The mathematics was clear enough: to convert a signal from the time domain to the frequency domain, you integrate from negative infinity to positive infinity. My practical engineering mind kept asking: “Can’t we just use a really large finite number? Why insist on actual infinity?”

The answer turned out to be more profound than I expected.

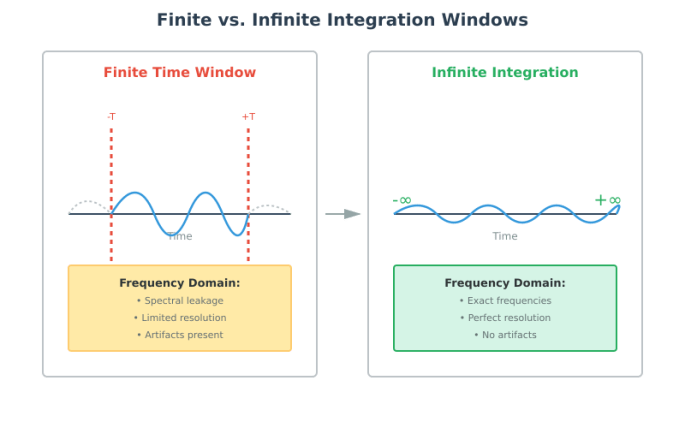

Try to use a finite window—say, measuring a signal for a very long but finite time—and something breaks. You don’t get an approximation that’s “close enough.” You get a fundamentally different result. The frequency representation becomes blurred, uncertain—essential frequencies morph into artifacts, real signals get masked by fictitious ones. It’s the mathematical equivalent of trying to read a book by examining individual letters through a microscope: you see detail, but you’ve lost the meaning.

This isn’t a limitation of our tools. It’s not that better instruments would solve the problem. The mathematics itself is telling us something: to perfectly understand a system’s behavior, you need the view from infinity.

Think of it like trying to understand a symphony’s theme from a single note. You get some information—pitch, volume, timbre—but you miss the essential structure. The melody, the harmony, the composer’s intent—these only emerge when you have the whole piece. Similarly, a signal’s true frequency structure only emerges through integration over infinite time.

“But surely,” you might object, “this is just a mathematical convenience. We’re using infinity as a useful fiction to make the calculations work, right?”

That’s what I thought too. Until I noticed that this pattern appears everywhere we look deeply into reality’s foundations.

GPS navigation relies on precise frequency analysis of satellite signals. The algorithms assume infinite-domain mathematics because finite approximations simply don’t work well enough. Your phone’s ability to pinpoint your location depends on treating infinity as real, not metaphorical.

Signal processing, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics, cosmology—the same pattern appears everywhere we look deeply into reality’s foundations, from the very small to the very large. Finite models give approximations that break down in crucial ways, while infinite models capture reality’s actual behavior.

This ubiquity demands explanation. Is infinity really just a computational trick we happen to use everywhere? Or is mathematics revealing something fundamental about the architecture of existence itself?

The question isn’t idle speculation. Because if our most reliable tools for understanding reality require infinite domains to function correctly, this might be telling us something essential about what they’re describing.

This observation launched a deeper investigation: is infinity merely convenient, or does it reveal something about reality’s architecture? And that hint—that mathematical evidence—points in the same direction as the logical argument we established previously: toward a reality whose ultimate foundation must be unlimited.

Let’s see just how deep this pattern goes.

Why Transform Theory Matters: Not Just Computational Tricks

Let me make the Fourier transform insight more concrete with an analogy.

Imagine trying to understand a symphony’s theme by listening to a single note. You’d hear pitch, volume, timbre—useful information. But the melody? The harmonic structure? The composer’s emotional arc? These only emerge when you have the complete piece, from opening bars to final crescendo.

This is precisely what happens with signal analysis. A finite time window gives you local information—what’s happening right now—but the global structure, the fundamental frequencies that characterize the entire signal, remain hidden. To reveal them requires integrating over infinite time.

“But surely,” a skeptic might press, “this is just mathematical idealization. Real signals are finite. Real measurements take finite time. Aren’t we just using infinity as a convenient fiction?”

This is where it gets interesting.

The Practical Test

Consider GPS navigation. Your phone receives signals from satellites orbiting 20,000 kilometers above Earth. To pinpoint your location within meters, the system must analyze these signals’ frequency content with extraordinary precision—errors of nanoseconds translate to errors of meters. This precision comes from correlating frequency shifts (due to satellite motion) against known codes, relying on the Fourier transform’s ability to resolve exact frequencies.

The algorithms don’t use finite-time approximations and accept the degradation. They’re designed around infinite-domain mathematics because that’s what actually works. When engineers tried using finite models in early development, the results were inadequate—not because of implementation errors, but because finite-time Fourier analysis introduces fundamental limitations.

The frequency precision you need requires the infinite integral. This isn’t theoretical abstraction—it’s why your navigation works.

What Actually Breaks

When you analyze a signal through a finite window, you don’t just get less precision. You get qualitatively different results:

Spectral leakage: Energy from one frequency “leaks” into adjacent frequencies, creating false signals where none exist—this could make your music app misidentify song genres based on phantom harmonics

Frequency resolution limits: You cannot distinguish between two close frequencies below a certain threshold determined by your window size

Artifacts and aliasing: Fictitious components appear that have no correspondence to the actual signal

These aren’t measurement imperfections that better instruments could overcome. They’re mathematical necessities. A finite window must produce these distortions. The only way to eliminate them completely is to extend the integration to infinity.

This reveals something profound: to perfectly understand a system’s behavior—to access its true structure—you need the view from infinity.

Figure 1: Finite-window Fourier analysis (left) captures only a limited time segment, introducing spectral leakage, resolution limits, and artifacts. Infinite integration (right) reveals exact frequency content without distortion. This isn’t just better approximation—it’s fundamentally different mathematics.

The Honest Objection: Finite Approximations Work

But here’s a fair challenge that deserves serious consideration: GPS systems use finite-time Fourier analysis and work excellently. Digital signal processing operates entirely on discrete, finite samples. Engineers achieve remarkable precision using finite methods every day. Why insist the infinite version captures “true” structure rather than being merely an idealization?

The response requires nuance. Finite methods work because they approximate the infinite case well enough for practical purposes. But “good enough for engineering” isn’t the same as “capturing the actual structure.”

Think about how we know finite methods work: we benchmark them against the infinite theory. We calculate how much error a finite window introduces by comparing it to the infinite case. We design optimal sampling rates by proving theorems about how finite samples can represent infinite continuous signals (the Nyquist-Shannon theorem). We troubleshoot problems in finite implementations by understanding where they diverge from infinite ideals.

The finite approaches are parasitic on—and derivative from—the infinite framework. They work precisely because they approximate something more fundamental.

When theoretical precision matters—deriving optimal algorithms, proving convergence theorems, understanding why our methods work rather than just that they work—we return to infinite analysis. The path of explanation runs from infinite to finite, not the reverse.

This doesn’t definitively prove infinity is “ontologically real” in some ultimate sense. But it does establish the direction of dependency: infinite models are conceptually primary, finite ones are practical simplifications.

The Pattern Extends Beyond Signals

The same principle appears wherever we look deeply into nature’s mathematical structure. In quantum mechanics, particle wavefunctions extend over infinite space even when particles are highly localized—essential to preserving the theory’s consistency, as we’ll explore further. In thermodynamics, phase transitions (like water freezing into ice) only occur as genuine discontinuities in the infinite limit.

Picture water transforming into ice: that sharp transition from liquid to crystal only emerges mathematically when we take the number of molecules to infinity. Finite systems show smooth transitions that approximate but never quite capture the phase boundary. This isn’t academic nitpicking—it’s why materials science can predict how metals behave under extreme conditions, relying on infinite limits for accurate phase diagrams.

In cosmology, observations from the Planck satellite’s cosmic microwave background measurements, supported by recent James Webb Space Telescope data confirming our cosmological models, suggest our universe is spatially flat—which in general relativity implies infinite extent, though finite but unbounded models remain possible.

From the quantum realm to the cosmic scale, from signal processing to statistical mechanics, the pattern repeats: finite models give us approximations, shadows, suggestions. Infinite models capture reality’s actual structure—or at least, they capture it more completely than any finite alternative we’ve discovered.

The Deeper Question

This ubiquity demands explanation. Why do infinite mathematical structures work better than finite ones for describing the physical world?

Three possibilities present themselves:

1. Coincidence or convenience: We happen to live in a universe where infinite mathematics works well as an approximation, even though reality is fundamentally finite. But this multiplies mysteries. Why would a finite reality be perfectly describable by infinite mathematics? Why wouldn’t finite models—which would directly mirror that finite reality—work better?

2. Pragmatic choice: Infinite models are simpler to work with mathematically, so we use them despite them being strictly false. But this is empirically false. Infinite models aren’t always simpler (they often require sophisticated limiting procedures), yet they consistently give better results. If this were just mathematical convenience, we’d expect cases where finite models excel. We don’t find them.

3. Structural tracking: Infinite mathematics works because it reflects something fundamental about reality’s architecture. When the tools that actually work all share a common feature—in this case, requiring infinite domains—the simplest explanation is that this feature tracks something real.

We find option (3) most plausible, though we cannot rule out (1) or (2) with absolute certainty. This is inference to the best explanation, not deductive proof. But the systematic pattern—infinite models working better across every fundamental domain—makes coincidence or mere convenience increasingly implausible.

This aligns with our earlier logical conclusion that any limit on the ground of being would require an external imposer—something infinity elegantly avoids. Just as a contingent universe begs “why this rather than that?”, a finite reality begs “why this limit?”—a question only an infinite ground answers coherently.

And if our mathematical descriptions of reality fundamentally require infinity, this suggests that reality itself has an infinite structure—at its ground, as our logical argument demands.

This mathematical evidence now points in precisely the same direction as our earlier logical reasoning: toward an ultimate foundation that cannot be bounded, cannot be limited, cannot be finite without raising the inescapable question: “Why this boundary rather than none?”

Let’s explore this pattern across physics—from quantum mechanics’ infinite-dimensional spaces to cosmology’s boundless universe—revealing why infinity appears as a feature of the ultimate reality we’ve logically deduced.

The Physical Evidence: Where Infinity Appears in Fundamental Physics

The pattern we’ve traced through transform theory isn’t isolated to signal processing or mathematical abstraction. When we examine the foundations of physics—the theories that best describe reality at every scale—we find infinity appearing not as a convenient idealization but as a structural necessity.

Let’s see what happens when we try to remove it.

The Collapse Test: What Breaks When We Remove Infinity

The clearest way to understand infinity’s role is to ask: what would change if we made our theories finite? Not just less accurate—fundamentally different:

| Theory/Concept | With Infinity | Without Infinity | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics | Uncertainty principle, exact wave-particle duality | No true uncertainty relation, superposition structure breaks | Fundamentally different theory—loses core features |

| Fourier Analysis | Perfect frequency resolution | Approximation only, spectral leakage | Cannot distinguish close frequencies precisely |

| Thermodynamics | Sharp phase transitions, true criticality | Smooth transitions only | No crystalline structures, different material properties |

| Field Theory | Well-defined boundary conditions at infinity | Ambiguous or inconsistent solutions | Electromagnetic theory breaks down |

These aren’t degraded versions of the same theories. They’re different theories entirely. The infinite versions don’t just work better—they work correctly in ways the finite versions fundamentally cannot.

This is the decisive evidence: finite models aren’t just worse versions of the same theories—they describe different realities entirely. If infinity were merely a computational convenience, finite models would give good approximations. Instead, removing infinity changes the theory’s basic structure.

What This Shows—And What It Doesn’t

The Collapse Test demonstrates that removing infinity gives qualitatively different theories, not just less accurate versions of the same one. This is strong evidence that infinity is structurally necessary in our models.

But we must be careful about what this proves. Necessary in our models doesn’t automatically mean necessary in reality itself. Three possibilities exist:

Instrumentalism: Infinite models are just efficient tools for approximating complex (but ultimately finite) reality

Epistemic necessity: Our cognitive architecture requires infinite structures to grasp reality, regardless of reality’s actual nature

Ontological tracking: The models require infinity because reality has infinite structure

We find (3) most plausible based on cumulative evidence, but we cannot rule out (1) or (2) definitively. Our argument builds through the systematic repetition of this pattern: as infinity appears structurally necessary across every fundamental domain, the “ontological tracking” hypothesis becomes increasingly parsimonious compared to alternatives that require cosmic coincidence or unexplained anthropic selection.

Let’s examine where this pattern appears across physics, noting both the strength of the evidence and its limitations.

Quantum Mechanics: Infinite Spaces as Necessity

Consider a single electron in a hydrogen atom. Where is it?

The quantum wavefunction spreads over all of space. The probability of finding the electron never exactly reaches zero, no matter how far from the nucleus you travel. This isn’t because we lack precision—it’s what the mathematics requires for the theory to be internally consistent.

Why must wavefunctions extend infinitely? Because of the uncertainty principle, which itself depends on infinite-dimensional Hilbert space. The precise mathematical relationship between position and momentum—the fact that you cannot know both exactly—emerges from Fourier duality. And as we’ve seen, Fourier duality only works perfectly in infinite domains.

Remove the infinite-dimensional structure, and you don’t just lose precision. You lose quantum superposition. You lose entanglement. You lose the wave-particle duality that defines quantum mechanics. In a finite-dimensional system, there’s an upper limit to how many distinct states can be superimposed. But quantum mechanics requires the possibility of infinite superposition—precisely what gives us the rich interference patterns we observe in every quantum experiment. The finite version isn’t “approximate quantum mechanics”—it’s classical mechanics in disguise.

This matters for modern physics. Quantum entanglement—Einstein’s “spooky action at a distance”—requires infinite-dimensional state spaces to function. When two particles become entangled, their combined state exists in a space that’s the tensor product of two infinite-dimensional spaces. You cannot capture entanglement’s non-local correlations in any finite model.

The vacuum itself tells the same story. In quantum field theory, what we call “empty space” isn’t empty at all—it’s a seething foam of virtual particles, an infinite-dimensional structure of quantum fluctuations. This isn’t speculation; these vacuum fluctuations create measurable effects like the Casimir force and the Lamb shift, both experimentally confirmed to extraordinary precision.

Important caveat: Some interpretations of quantum mechanics avoid infinite spaces. Consistent histories formulation and some versions of quantum logic use finite-dimensional structures. However, these typically sacrifice predictive power or explanatory completeness. The infinite-dimensional framework remains dominant because it works best—though “best” doesn’t necessarily mean “true” in an ontological sense.

Thermodynamics: Phase Transitions at Infinity

Why does water freeze at exactly 0°C? Why do magnets lose their magnetism at a precise Curie temperature? These sharp phase transitions—discontinuous changes in material properties—only appear mathematically when we take the thermodynamic limit: the number of particles approaching infinity.

Real systems are finite, of course. But they approximate the infinite limit so closely that the predictions work. A glass of water contains roughly 10²⁵ molecules—close enough to infinity for practical purposes that ice really does form at a sharp boundary.

The deeper point: the crisp, stable properties of matter that make the physical world predictable emerge from infinite mathematics. The crystalline structure of diamonds, the liquid flow of water, the gaseous expansion of air—these distinct phases with their sharp boundaries are shadows of infinite limits. This isn’t academic nitpicking—it’s why materials science can predict how metals behave under extreme conditions, relying on infinite limits for accurate phase diagrams.

Classical Fields: Infinity as Foundation

Maxwell’s equations, which govern all electromagnetic phenomena from radio waves to X-rays, have solutions that extend to spatial infinity. The uniqueness theorems—the proofs that a solution is the only solution given certain conditions—depend critically on specifying boundary conditions “at infinity.”

Without infinite spatial extent, electromagnetic theory becomes ambiguous. You can’t uniquely determine electric and magnetic fields, which means you can’t calculate how light propagates, how circuits behave, or how electromagnetic waves travel. The theory doesn’t just become harder—it becomes incomplete.

Special Relativity: Infinite Symmetries

Special relativity’s Lorentz transformations form what mathematicians call a continuous group—an infinite-dimensional structure. The smooth way that space and time transform between reference frames requires infinite parameters to describe completely.

More tellingly, the energy-momentum relation E² = p²c² + m²c⁴ allows for unbounded energy. Give a particle enough momentum, and its energy grows without limit. There’s no ceiling, no maximum. The mathematics suggests infinite “headroom” in reality’s structure.

Cosmology: Spatial Infinity as Measurement

The Planck satellite’s observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation—the afterglow of the Big Bang—constrain the universe’s spatial curvature to within 0.4% of flatness. In general relativity, a flat universe is spatially infinite.

This is suggestive, not conclusive. Finite but unbounded topologies remain mathematically possible (like a 3-dimensional version of a video game that wraps around at the edges). But the simplest interpretation of the data points toward infinite spatial extent.

If our universe is actually spatially infinite, this isn’t just a large size—it’s a qualitatively different kind of reality. It means there’s no edge, no boundary, no “end” to space. Reality doesn’t terminate; it continues without limit in every direction.

However, recent work in digital physics, loop quantum gravity, and holographic principles suggests reality might be fundamentally discrete at Planck scales. This is serious physics, not fringe speculation. Loop quantum gravity makes spacetime discrete at the smallest scales, potentially avoiding infinities in quantum gravity. The holographic principle suggests the information content of any region is finite, proportional to its surface area rather than volume.

Our argument must acknowledge these developments. They represent genuine alternatives to infinite models, pursued by serious physicists addressing real theoretical problems. The fact that even discrete proposals typically embed in infinite mathematical frameworks for consistency suggests the pattern we’re tracing runs deep—but it doesn’t make competing approaches invalid.

The Unifying Pattern

Across every domain—from the quantum foam to cosmic horizons—infinity appears not as a mathematical accident but as structural necessity:

Remove infinity from quantum mechanics, and the theory collapses into something fundamentally different

Remove infinity from thermodynamics, and phase transitions vanish

Remove infinity from field theory, and uniqueness disappears

Remove infinity from relativity, and symmetries break

Remove infinity from cosmology, and the simplest model fails

This isn’t cherry-picking favorable examples. These are the foundations of modern physics—our best-tested, most successful theories. And they all require infinity to work correctly.

The pattern is unmistakable. When we describe reality with mathematics that actually captures its behavior, that mathematics is infinite. When we try finite models, they fail in fundamental ways—not just quantitatively but qualitatively.

This suggests something profound: the mathematical structure isn’t arbitrary. It’s tracking something real about the architecture of existence itself.

And that architecture appears to be infinite all the way down.

Yet a skeptical voice remains: “Aren’t these just mathematical tools—useful fictions that happen to work?” Let’s examine this objection directly, because it reveals something crucial about the relationship between mathematics and reality.

Addressing the “Just a Mathematical Tool” Objection

The most sophisticated objection to our argument doesn’t deny that infinity appears everywhere in physics. It challenges what this appearance means.

“These infinities,” the objection runs, “are useful fictions—calculational conveniences that make the mathematics tractable. They’re not ontological commitments about reality itself. We use infinite models because they’re easier to work with, not because reality is actually infinite.”

This sounds reasonable. After all, physicists routinely use idealizations that aren’t literally true. We treat Earth as a perfect sphere for many calculations, knowing it’s actually oblate. We model gases as continuous fluids, ignoring their atomic structure. Why shouldn’t infinity be another useful approximation?

The answer lies in a crucial distinction.

Part 1: Useful vs. Structurally Necessary

Some mathematical tools are dispensable. Replace them with more accurate models and you get better results. Treat Earth as an oblate spheroid instead of a perfect sphere, and your orbital calculations improve. Model gases at the molecular level instead of as continuous fluids, and you capture behavior the continuum approximation misses.

These are approximations in the genuine sense—shortcuts that sacrifice precision for convenience.

But infinity in fundamental physics isn’t like this at all.

The Collapse Test from the previous section demonstrated something crucial: removing infinity doesn’t give you a less accurate version of the same theory. It gives you a different theory that fails in fundamental ways. Without infinite-dimensional Hilbert space, quantum mechanics doesn’t become “approximate quantum mechanics”—it becomes classical mechanics. Without the thermodynamic limit, phase transitions don’t become fuzzy—they disappear entirely.

This is the key distinction: infinity isn’t like assuming a spherical cow to make calculations easier. It’s like needing numbers to do arithmetic.

Try to develop physics without infinity, and you can’t capture the phenomena we actually observe. The theory doesn’t just become harder to work with—it becomes unable to describe reality as we find it.

Part 2: Why Instrumentalism Remains Viable

Yet we should acknowledge: many working physicists are instrumentalists about infinity. They use the mathematics without metaphysical commitment. This position isn’t naive—it’s philosophically defensible and pragmatically successful.

The instrumentalist says: “Infinite models work better because they’re mathematically simpler and more elegant, not because reality is infinite.” This view has genuine support:

Precedent for useful fictions: Science has historically employed idealizations that worked despite being false (epicycles predicted planetary motion accurately for centuries)

Limits of observation: We can’t directly observe infinity—all measurements are finite

Methodological parsimony: Why multiply ontological commitments beyond what’s strictly necessary for predictions?

These aren’t weak objections. They represent a coherent philosophical stance with respectable pedigree.

So why do we still find ontological commitment to infinite structure more plausible?

The pattern is too systematic. If infinite math were just convenient, we’d expect some domains where finite models excel. Instead, across quantum mechanics, field theory, thermodynamics, and cosmology, infinite models consistently outperform finite ones. When theories become more sophisticated (quantum field theory, string theory), infinity persists or deepens rather than being eliminated—suggesting it’s structural rather than artifactual.

The convenient fiction hypothesis multiplies mysteries. If reality is fundamentally finite, why does it require infinite mathematics universally? Why wouldn’t finite models—which would directly mirror finite reality—work better? The instrumentalist needs to explain this systematic asymmetry. We’re not claiming certainty, but inference to the best explanation favors: infinite mathematics works because it tracks infinite structure.

The direction of theoretical development matters. When physicists encounter problematic infinities (like divergences in quantum field theory), they don’t typically solve them by making theories finite. They develop better ways to handle infinity (renormalization) or propose theories with richer infinite structure (string theory’s extra dimensions). This pattern suggests infinity is being refined rather than eliminated.

This doesn’t decisively refute instrumentalism. It shows why we find the “ontological tracking” hypothesis more parsimonious given the cumulative evidence. But readers who remain instrumentalists can still appreciate the mathematical pattern—they’ll just interpret its significance differently.

Part 3: The Anthropic Selection Argument—Taken Seriously

A more subtle objection deserves careful attention: “Perhaps we evolved to discover only mathematics that works in our specific universe. Infinite structures might be ‘local’ to our reality rather than fundamental to all possible realities. The apparent necessity of infinity reflects anthropic selection, not metaphysical truth.”

This is a sophisticated challenge that we cannot dismiss lightly. It proposes that the mathematics-reality fit we observe is explained by selection effects: only universes describable by certain mathematical structures could produce observers, so observers necessarily find those structures.

We offer three responses, with appropriate humility:

First, the historical sequence cuts against it. Pure mathematics developed infinite structures—Hilbert spaces, Fourier analysis, continuous symmetry groups—before their physical applications, often by decades or centuries. Fourier developed his transform for understanding heat flow in the early 1800s. Hilbert developed his spaces for abstract mathematical analysis in the early 1900s. Only later did physicists discover these structures describe quantum mechanics and signal processing with uncanny accuracy.

If we were simply inventing mathematics to fit our local universe, we’d expect the physics to come first and the math to follow. Instead, abstract mathematics anticipated physical applications—suggesting we discovered something fundamental rather than constructed something contingent.

Second, Wigner’s observation about the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics” cuts directly against the anthropic argument. If mathematical structures were just tools we shaped to fit our local physics, their effectiveness wouldn’t be unreasonable—it would be tautological, expected by construction. The fact that physicists find this effectiveness surprising and mysterious suggests the relationship isn’t one of convenient construction but genuine discovery.

If the anthropic argument were correct, the fit between mathematics and physics should seem obvious and expected. Instead, physicists find it puzzling. This puzzlement itself is evidence against anthropic selection as the full explanation.

Third, the argument cuts both ways. If only certain mathematical structures support observers, this doesn’t explain why those particular structures (infinite ones) are the life-permitting ones. Why should observer-permitting universes specifically require infinite mathematics? The anthropic principle pushes the question back one level without answering it.

Moreover, even multiverse theories—often invoked to explain fine-tuning through selection effects—typically invoke infinite ensembles of universes to explain why we observe this particular configuration. The infinity doesn’t disappear; it just moves up one level of abstraction.

We claim only: anthropic selection doesn’t defeat the argument, though it prevents overconfidence. The pattern remains: infinite mathematics works systematically better than finite alternatives, and this needs explanation.

Part 4: The “Breaking Down” Response—Nuanced

“But physicists treat infinities as pathologies!” the objection continues. “Renormalization in quantum field theory removes infinities. When divergences appear in calculations, it signals the theory’s breaking down. This proves they’re artifacts of the mathematics, not features of reality.”

This objection deserves a nuanced response, because it gets something right: physicists do view certain infinities as problematic.

But this cuts both ways.

Renormalization isn’t about eliminating infinity from theory—it’s about handling infinities correctly within infinite frameworks. The renormalized quantum field theories still operate in infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces. They still require infinite integrals. What renormalization does is show that certain divergent quantities can be absorbed into physical parameters (like mass and charge) rather than appearing as nonsensical infinite predictions.

This is about making the mathematics work properly within an infinite structure, not replacing infinity with finitude.

When physicists encounter truly problematic infinities they can’t handle, the solution isn’t typically to make theories finite. String theory, developed partly to resolve infinities in quantum gravity, operates in even higher-dimensional spaces (10 or 11 dimensions, depending on the version)—still infinite in mathematical structure, just differently structured. Loop quantum gravity, an alternative approach, might make spacetime discrete at the Planck scale, but still embeds in infinite mathematical frameworks for consistency.

The persistence of infinity across theory revisions—from classical mechanics to quantum mechanics to quantum field theory to proposed theories of quantum gravity—suggests something structural rather than accidental. If infinity were just a calculational convenience that could be eliminated, we’d expect at least some successful formulations to be finite. We don’t find them.

However, we must acknowledge: perhaps we simply haven’t discovered the right finite framework yet. Loop quantum gravity and digital physics remain active research programs. The history of physics includes cases where apparent necessities turned out to be artifacts of inadequate conceptual frameworks.

Our claim is probabilistic, not certain: the systematic persistence of infinity across theoretical improvements suggests structural depth rather than eliminable artifact. But future physics could surprise us.

Part 5: Predictive vs. Descriptive Success

“But predictions work with finite approximations!” comes the pragmatic objection. “Engineers use finite Fourier transforms every day. Quantum computers operate with finite-dimensional state spaces. If finite models give good-enough predictions, why insist on ontological infinity?”

This objection conflates two different things: predictive adequacy for practical purposes versus theoretical completeness.

Yes, you can approximate infinite models with finite ones and get predictions accurate enough for engineering. GPS works with finite-time signal analysis by accepting some error. Quantum computers approximate infinite-dimensional quantum mechanics within finite hardware.

But notice: these finite approximations are always benchmarked against the infinite theory. We know how much error the finite window introduces in Fourier analysis because we can compare it to the infinite case. We design quantum computers to approximate specific infinite-dimensional quantum systems. The finite methods are evaluated by how well they approach infinite ideals.

The infinite model isn’t an idealization of finite reality—the finite approximations are pragmatic simplifications of infinite reality. The direction of explanation matters.

Moreover, when precision really matters—in fundamental tests of quantum mechanics, in precision measurements of fundamental constants, in cosmological observations—the infinite models give more accurate predictions than finite ones. If this were just about mathematical convenience, we’d expect some domains where finite models excel. We don’t find them.

Part 6: The Computational Simulation Test

Here’s a decisive test: Can finite computer simulations fully capture infinite systems?

The answer is definitively no. Finite computers can approximate infinite systems to arbitrary precision given enough resources, but they cannot exactly replicate behavior that depends on true infinity. Phase transitions, critical phenomena, certain quantum effects—these show qualitative differences between finite approximations and infinite limits, no matter how large you make the finite system.

If infinite mathematics were just a convenient fiction, computational approaches should eventually match or surpass infinite models. More powerful computers, better algorithms, clever approximations—these should close the gap.

They don’t. The gap persists because it’s not computational but structural.

This doesn’t prove infinity is ontologically real—perhaps reality itself has computational limits we’re discovering. But it does show that infinite models capture something finite computational approaches cannot, even in principle.

The Cumulative Force

None of these responses alone is decisive. But together, they create cumulative pressure:

| Objection | Response | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| “Useful fiction” | Structurally necessary, not dispensable | Theories collapse without it |

| “Anthropic selection” | Math preceded physics | Suggests discovery, not construction |

| “Renormalization removes infinity” | Manages infinity, doesn’t eliminate | New theories preserve infinite structure |

| “Finite approximations work” | Benchmarked against infinite theory | Direction of explanation matters |

| “Computers approximate well enough” | Gap persists structurally | Not computational but ontological issue |

The simplest explanation for all these facts together is that mathematical infinity tracks something real about reality’s structure. Not because we’ve proven this with certainty, but because every alternative explanation multiplies mysteries.

If reality were fundamentally finite but perfectly described by infinite mathematics across all domains, this would be the most remarkable coincidence in the history of science. If infinite mathematics just reflects our local physics, why did it develop before its applications? If infinity is a dispensable tool, why do theories fail fundamentally when we remove it?

The pattern is clear: when we use mathematics that assumes infinite structure, we capture reality’s behavior. When we try to avoid infinity, our descriptions break down.

This strongly suggests that infinity isn’t merely in the mathematics—it’s in what the mathematics describes.

But strong suggestion isn’t proof. We’ve now traced the mathematical pattern and addressed the major objections. The question remains: does mathematical necessity in our models tell us something about metaphysical reality? That requires us to bridge from mathematical infinity to metaphysical infinity—carefully and with clear acknowledgment of the inferential gap.

From Mathematical Infinity to Metaphysical Infinity

We’ve established that infinity appears structurally necessary in our mathematical descriptions of reality. But what kind of infinity are we talking about? And what does mathematical necessity tell us about the ultimate nature of existence?

These questions matter because “infinity” means different things in different contexts, and conflating them leads to confusion—and to unwarranted conclusions.

Three Types of Infinity—And Why We Must Distinguish Them

Mathematical infinity refers to formal properties within mathematical systems. When we say there are infinitely many integers, or that Hilbert space is infinite-dimensional, or that an integral extends to infinity, we’re making precise statements within mathematical structures. These infinities come in different varieties—countable (like integers), uncountable (like real numbers), or the infinite dimensions of function spaces. Hilbert’s famous hotel paradox captures this: a hotel with infinitely many rooms can always accommodate another guest by shifting everyone up one room.

Physical infinity describes properties of spacetime or physical systems. An infinitely extended universe, unbounded energy in the relativistic energy-momentum relation, or infinite-dimensional quantum state spaces fall into this category. These represent claims about how reality is structured at the physical level—how much space exists, what range of values physical quantities can take, how many dimensions describe quantum states.

Metaphysical infinity points to something more fundamental: the ground of being’s lack of limitations or determinations. This isn’t “infinite” in the sense of counting or measuring—it’s unlimited in the sense of having no boundaries, no specific constraints, no determinate characteristics that would make it “this rather than that.” It’s infinity understood as the absence of finitude, not as an extremely large quantity.

Conflating these is the central vulnerability of our argument. That Hilbert spaces are infinite-dimensional (mathematical) doesn’t automatically prove spacetime is infinite (physical), much less that the ground of being is unlimited (metaphysical).

The connection requires careful steps—and we must be honest about the inferential gaps.

The Inferential Chain—Made Explicit

Here’s the logical structure, with each step’s strength indicated:

Mathematical infinity appears structurally necessary in our models (established in previous sections) — Strong empirical support

This suggests (but doesn’t prove) that what we’re modeling has infinite structure — Inference to best explanation; instrumentalist alternatives remain viable

If physical reality exhibits infinite structure, this is consistent with—though doesn’t entail—an unlimited metaphysical ground — Weak inference; the gap between physical and metaphysical is substantial

The logical argument (next section) independently establishes that the ground must be unlimited — Strong deductive argument from premises about necessary being

The mathematical evidence provides convergent support from a different angle — Moderate support; convergence is significant but not conclusive

The mathematical case is suggestive, not demonstrative. Its value lies in showing that infinity isn’t merely a logical abstraction—it appears concretely in our best empirical descriptions of reality. But we must be clear: this is cumulative, probabilistic reasoning, not deductive proof.

Why Mathematics Points Beyond Itself—Carefully

Whether mathematical structures are discovered (Platonism) or invented (nominalism) affects how we interpret the pattern, but doesn’t eliminate the explanatory puzzle.

If Platonism is true: Mathematical objects exist independently in some abstract realm. The fact that infinite mathematical structures (real numbers, Hilbert spaces, continuous groups) accurately describe physical reality suggests that both the mathematical realm and physical reality share some common infinite ground. If mathematics is discovered rather than invented, then its infinite nature points toward something infinite being discovered.

If nominalism is true: Mathematics is human construction shaped by our interaction with reality. Yet even as construction, we consistently find that infinite structures are most effective for modeling reality. This needs explanation. Why would finite reality require infinite mathematics universally? Why wouldn’t finite models—which would directly mirror finite reality—work better?

Either way, we face the same puzzle: Why does infinite mathematics capture reality better than finite mathematics if reality is fundamentally finite?

The most parsimonious answer: it doesn’t. The mathematics tracks structure—infinite mathematics works because it reflects infinite structure.

But we must acknowledge: this is inference to the best explanation, not deductive proof. Alternative explanations remain possible:

Infinite math might be an efficient approximation of irreducible complexity

Cognitive constraints might force us toward infinite structures regardless of ontology

We might simply lack the conceptual framework for a successful finite theory

These alternatives are logically coherent. We find them less plausible based on systematic patterns, but “less plausible” isn’t “impossible.”

Wigner’s Unreasonable Effectiveness—Revisited

Eugene Wigner’s famous observation deserves attention here. He noted that mathematics is “unreasonably effective” in describing physical reality—more effective than we have any right to expect if mathematics were merely human invention with no connection to reality’s deep structure.

This observation cuts against the anthropic selection argument. If we simply evolved to develop mathematics that works in our local environment, the effectiveness wouldn’t be unreasonable—it would be tautological, expected by construction. The surprise physicists express at mathematics working so well suggests we’re discovering something fundamental rather than constructing something contingent.

Moreover, Wigner noted that the same mathematical structures keep appearing across disparate physical domains—the same differential equations govern heat flow, quantum mechanics, and financial derivatives. This unity suggests mathematics taps into something structural about reality, not just convenient descriptions we’ve invented.

But Wigner himself didn’t claim this proved mathematical Platonism or metaphysical infinity. He presented it as a mystery requiring explanation. We’re suggesting that an infinite ground provides that explanation—but this remains hypothesis rather than established fact.

The Key Insight: Mathematical Infinities as Reflections

Here’s the crucial move, stated carefully:

Mathematical infinities in our theories may be shadows or reflections of the metaphysical infinity of their ground.

Not proof, but suggestive pattern. If the ultimate foundation of reality is unlimited (as the logical argument will establish), we might expect that:

Physical theories describing what emerges from this ground would involve infinite structures

Mathematical frameworks capturing this physics would require infinite domains

Attempts to remove infinity would fundamentally break the theories

This is exactly what we observe. The pattern doesn’t prove the hypothesis, but it’s consistent with it in ways that would be remarkable coincidence if false.

Think of it this way: if the ground of being were finite—bounded by specific limits—why would infinite mathematics be necessary to describe what emerges from it? Why wouldn’t finite models work better for finite reality? The mathematics itself seems to be telling us something about its subject matter.

What This Connection Means—And Doesn’t Mean

This argument does NOT establish:

That physical spacetime is literally infinite in extent (remains an open empirical question)

That mathematical objects exist in some Platonic realm

That “infinite” means “spatially unbounded” rather than some other sense of unlimited

That we can directly perceive or access metaphysical infinity through mathematical study

This argument DOES suggest:

Mathematical necessity and metaphysical necessity point in the same direction

The systematic requirement for infinite structures in physics is non-arbitrary

The “ontological tracking” hypothesis is more parsimonious than alternatives requiring cosmic coincidence

Logic and mathematics provide convergent (though not conclusive) evidence for unlimited ground

The mathematical pattern supports but doesn’t prove the metaphysical conclusion. Think of it as circumstantial evidence in a legal case—not sufficient alone for conviction, but meaningful when combined with direct evidence (the logical argument).

The Honest Assessment of This Bridge

We’ve now traced mathematical infinity through fundamental physics and addressed why it’s not merely a convenient fiction. But the bridge from mathematical to metaphysical infinity has genuine gaps:

Gap 1: Models requiring infinity doesn’t automatically mean reality is infinite—instrumentalism remains viable

Gap 2: Physical infinity (if real) doesn’t automatically imply metaphysical infinity—these are different categories

Gap 3: Even if the ground is metaphysically infinite, this doesn’t tell us how it manifests in physical/mathematical structures

These gaps are real. We’re not claiming airtight proof from mathematics to metaphysics.

What we are claiming: when mathematical necessity, physical structure, and logical argument all point toward infinity, this convergence from independent methods carries evidential weight. Not certainty, but reasonable confidence based on cumulative patterns.

The strongest case comes next: the pure logical argument for why the ground of being specifically must be unlimited. That argument stands independently. The mathematical evidence we’ve traced provides convergent support—showing that infinity isn’t just logically necessary but empirically manifest in our best descriptions of reality.

Let’s now make that logical case explicit.

Why the Ground of Being Specifically Must Be Infinite

We’ve traced infinity through mathematics and physics, showing it appears structurally necessary in our best descriptions of reality. But the strongest case for an infinite ground comes from pure logic, independent of empirical evidence.

This section presents two distinct arguments: first, the deductive logical case that stands alone; second, how the mathematical evidence provides convergent support from a different angle.

The Pure Logical Argument (Deductive)

This argument follows directly from what we established about necessary being in our previous piece. It requires no appeal to mathematical physics—just careful reasoning about what “necessary” and “unlimited” must mean.

The Argument:

The ground of being is necessary—it couldn’t fail to exist (established in previous piece)

Anything that has limits or boundaries must have those limits for some reason

That reason is either (a) imposed by something external, or (b) intrinsic to the thing’s nature

Nothing is external to the ground of being (by definition—it’s ultimate reality)

Could the limits be intrinsic—necessary to the ground’s own nature?

No—because any specific limit raises the question: “Why this limit rather than another?”

Even if a limit is claimed to be “intrinsic,” its specificity suggests alternatives that could have obtained

But anything that could have been otherwise is contingent, not necessary

Therefore, the ground cannot have specific limits

Therefore, it must be unlimited—infinite in the metaphysical sense

Why This Is Airtight:

The key insight is that specificity implies contingency. Whenever we have “this rather than that,” we have something that could have been otherwise. And anything that could have been otherwise requires explanation.

If the ground of being could only support universes with certain kinds of physical laws, we ask: why these laws rather than others? If consciousness could only exist up to a certain complexity, we ask: why that threshold? If reality had some specific boundary, we ask: why there rather than elsewhere?

These questions don’t stop until we reach something that genuinely has no specific determinations—something unlimited.

Addressing the Serious Counter-Objection

A thoughtful critic might respond: “Couldn’t a necessary being have intrinsic, necessary limits as part of its essential nature—limits that don’t require external explanation because they’re built into what it fundamentally is? Just as a triangle necessarily has three sides (not four), perhaps the ground necessarily has certain limits.”

This objection deserves careful response.

The triangle analogy actually undermines the objection. A triangle’s three-sidedness isn’t a contingent fact about triangles—it’s what “triangle” means. But this works only because triangles are defined entities within a broader geometric framework. The concept “triangle” is carved out from the space of possible polygons by stipulative definition.

The ground of being is categorically different. It’s not a defined entity within a broader framework—it is the framework. It’s not one kind of thing among other possible kinds—it’s the source of all kinds.

For the ground to have necessary intrinsic limits, those limits would have to be like the triangle’s three-sidedness—definitional, not contingent. But this creates a dilemma:

Horn 1: If the limits are truly definitional (like “triangle has three sides”), then we’re not talking about the ultimate ground—we’re talking about something defined within a broader logical space. That broader space, which includes the possibility of different definitions, would be more fundamental.

Horn 2: If the limits aren’t definitional but are somehow “just built in,” we’re back to the original problem: why these specific limits rather than others? The claim that they’re “intrinsic” doesn’t answer the question—it just labels it.

The difference is this: geometric objects like triangles have necessary properties because they’re abstractions carved out from mathematical space. The ground of being isn’t an abstraction—it’s what makes abstractions possible. It can’t have necessary limits in the same way because there’s no broader space from which it’s being carved out.

The “Why This Boundary?” Question—Applied Systematically

Let’s apply this reasoning to specific examples to see why any limit fails:

Spatial limits: Suppose reality could only extend to a certain spatial boundary. Why that boundary rather than one meter further? Or ten meters? Or infinite? The specific boundary is arbitrary unless something determines it. But what could determine a limit on ultimate reality itself?

Complexity limits: Suppose the ground could only support entities up to a certain complexity level. Why that level rather than higher or lower? What principle sets the threshold? If the principle is external, the ground isn’t ultimate. If it’s internal, why is it necessary rather than contingent?

Qualitative limits: Suppose certain qualities (consciousness, mathematical structure, physical law) could only exist in certain forms. Why these forms rather than others? Why these qualities rather than different ones? Every specific determination invites the same question.

The pattern is inescapable: any limit generates the question “why this limit?” which can only be answered by appealing to something more fundamental than the limit itself.

Only Unlimited Being Can Be Truly Necessary

Here’s the crucial connection: necessity requires the absence of alternatives. Something is necessary when it couldn’t be otherwise.

But anything with specific limits could be otherwise—it could have different limits, or no limits at all. The specificity of the limit proves it’s contingent.

Only something without determinate characteristics can be genuinely necessary in the required sense. Only unlimited being avoids the “why this rather than that?” question.

This isn’t arbitrary philosophical stipulation. It’s following the logic of necessity to its conclusion. If the ground could have been different, it’s not truly necessary. If it’s truly necessary, it cannot have been different. And if it cannot have been different, it cannot have had specific, contingent limits.

Connection to Classical Arguments

This reasoning echoes insights from multiple philosophical traditions, though we’re not depending on their authority:

Anselm’s ontological argument proposed “that than which nothing greater can be conceived.” While we don’t rely on conceivability arguments, the insight has force: any limited being can be exceeded by conceiving an unlimited one. The truly ultimate must be unlimited, or something beyond it (the unlimited) would be greater.

We can frame this more rigorously: a limited ground of being is less explanatorily adequate than an unlimited one. It raises questions (why these limits?) that it cannot answer. An unlimited ground answers those questions by transcending them—it has no limits requiring explanation.

Spinoza’s infinite substance was characterized as having infinite attributes, unlimited and unconditioned. Spinoza argued that any limitation would make something dependent on what limits it, contradicting its status as substance (self-subsistent reality).

The Vedantic Brahman is described as unlimited being-consciousness-bliss, without boundaries or determinations—not as theological doctrine but as logical necessity for ultimate ground.

These traditions converged on the same conclusion through independent reasoning: ultimacy requires unlimitedness. We’re following the same logical path, now with additional support from mathematical physics.

Where the Logical Argument Stands

This logical case is the foundation of our claim. It’s deductive reasoning from the premises:

The ground of being is necessary (from previous argument)

Necessity excludes contingency

Specific limits are contingent

Therefore the ground has no specific limits

If you grant the premises, the conclusion follows necessarily. This is stronger than the mathematical argument because it doesn’t depend on empirical patterns or inferences about what models track—it’s pure logical necessity.

The mathematical evidence we’ve traced becomes relevant here not as proof but as confirmation: logic says the ground must be unlimited; mathematics shows that describing reality requires unlimited structures. These aren’t coincidentally pointing the same direction—they’re investigating the same reality from different angles.

The Mathematical Evidence as Convergent Support

Now we can see how the mathematical pattern fits with the logical necessity:

Logic says: The ground of being cannot have limits (anything limited is contingent, not necessary)

Mathematics says: Our fundamental descriptions of reality require infinite domains to work correctly

Physics says: Attempts to remove infinity produce fundamentally different (and worse) theories

These aren’t three random facts. They’re three perspectives on the same underlying truth, and they converge.

If the ground were finite:

Logic predicts we’d face insoluble “why this limit?” questions (we do face them with finite models)

We’d expect finite models to work better for finite reality (they don’t)

We’d expect infinity to be optional in some theoretical formulations (it isn’t)

The convergence isn’t proof—logic alone establishes the conclusion. But it’s significant confirmation. When independent methods (deductive logic, mathematical necessity, empirical physics) all point toward infinity, parsimony suggests they’re tracking truth rather than coincidentally aligning.

Figure 2: Two independent paths converge on metaphysical infinity. The logical argument (right) is deductively strong; the mathematical evidence (left) provides inductive support. Together they triangulate on the same conclusion from different angles.

What “Infinite” Means Here

To be clear about what we’re claiming: the ground of being is infinite in the sense of being unlimited—without boundaries, without determinate characteristics that would make it “this rather than that.”

This doesn’t mean:

“Very large” in size

“Extending forever” in space

“Containing infinite quantities” of things

Those are physical or mathematical infinities. The metaphysical infinity of the ground is more fundamental: it’s the absence of any limiting principle whatsoever.

Think of it as the difference between:

“An ocean with no shore” (physical infinity—still a specific kind of thing)

“The capacity for oceans to exist at all” (metaphysical infinity—the unlimited source)

The ground isn’t an infinite thing. It’s the unlimited source from which all things arise. It has no specific characteristics because having specific characteristics would make it “this rather than that”—would make it limited, contingent, requiring explanation.

This is why philosophical traditions speak of it as “formless,” “unconditioned,” “absolute,” or “without characteristics.” These aren’t mystical evasions but precise attempts to point toward something that cannot be captured by finite concepts, because it is the precondition for all finite things.

The Convergence Is Not Coincidental

When logic demands unlimited ground, when mathematics requires infinite domains, when physics breaks down without infinite structures—this convergence demands explanation.

Three completely independent approaches:

Deductive logic about necessary being

Mathematical modeling of physical reality

Empirical physics describing observed phenomena

All three point toward infinity. Not vaguely, not metaphorically, but systematically and specifically.

The skeptic needs to explain this convergence. Why would:

Pure logic about necessary being point toward unlimited

Mathematical physics require infinite structures

Empirical success favor infinite models over finite ones

…all coincidentally, if reality’s ground is actually finite?

The simplest explanation: they’re not coinciding—they’re triangulating on truth. We’re glimpsing the same fundamental reality from multiple angles, and it appears unlimited from every vantage point we examine it from.

Remaining Uncertainty

Even this strong argument leaves questions open:

We don’t know:

How metaphysical infinity relates to physical infinity (or if our universe is physically infinite)

Whether “unlimited” means spatially unbounded or some other sense

How consciousness relates to this infinite ground (if at all)

Why unlimited being manifests as this particular physical universe

We claim only:

The logical argument for unlimited ground is deductively sound

Mathematical necessity provides convergent evidence

Together they create a strong cumulative case

Alternatives (finite ground, contingent universe as ultimate) face harder problems

This is rational confidence based on systematic evidence, not certainty that forecloses questioning.

The ground of being must be infinite. The mathematics confirms what logic demands. And this transforms how we understand everything that emerges from that unlimited foundation.

Addressing Remaining Objections

We’ve handled the major “just a tool” objection in depth, but several technical and philosophical concerns deserve direct attention. Let’s address them systematically.

Objection 1: “Renormalization Shows Physicists Remove Infinities”

The Objection: “Quantum field theory had problems with infinities appearing in calculations. Renormalization solved this by removing them. Doesn’t this prove infinities are mathematical artifacts rather than physical realities? When infinities appear in physics, they signal the theory breaking down.”

Response: This fundamentally misunderstands what renormalization accomplishes.

Renormalization doesn’t eliminate infinity from the theory—it shows how to handle infinities correctly within infinite frameworks. The renormalized quantum field theories still operate in infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces. They still require infinite integrals. They still describe infinite possibilities in state space.

What renormalization does is demonstrate that certain divergent quantities can be reinterpreted as corrections to measurable parameters like mass and charge, rather than appearing as nonsensical infinite predictions. It’s about making the mathematics work properly within an infinite structure, not replacing infinity with finitude.

Consider the analogy: when engineers discovered that certain bridge designs created destructive resonances, they didn’t conclude “bridges are impossible”—they developed better understanding of how to build bridges correctly. Similarly, when physicists found problematic infinities in quantum field theory, they developed better ways to handle infinite structures, not arguments for making theories finite.

Moreover, when physicists encounter truly problematic infinities they can’t manage through renormalization, the solution isn’t to make theories finite. String theory, developed partly to resolve infinities in quantum gravity, operates in even higher-dimensional spaces (10 or 11 dimensions, depending on the version)—still infinite in mathematical structure. The persistence of infinity across theoretical improvements suggests it’s structural, not artifactual.

However, we should acknowledge: the fact that infinities can be problematic shows they’re not always benign. Perhaps some infinities in our theories do signal incompleteness. This doesn’t undermine the argument that infinite structures are necessary—it just shows we need to understand which infinities are structural and which are artifacts of inadequate formulations.

Objection 2: “We Only Measure Finite Things”

The Objection: “All actual measurements are finite. We measure finite distances, finite times, finite energies. We can only ever count finite numbers of particles. If we only encounter finite quantities in practice, why insist reality is fundamentally infinite?”

Response: Measurement limitations don’t determine ontology. This objection confuses what we can observe with what must be true for our observations to make sense.

We also only measure discrete things (individual particles, distinct events), but continuous mathematics works better than discrete mathematics for fundamental physics. We can’t measure between Planck length scales, but that doesn’t prove space is necessarily discrete. We can’t measure velocities exceeding light speed, but that doesn’t mean the relativistic equations allowing mathematically unbounded energy are wrong.

The key point: infinite mathematical models make better predictions about the finite measurements we actually perform. If reality were fundamentally finite at its foundation, we’d expect finite models to work better—they would directly mirror the finite structure. The fact that infinite mathematics consistently outperforms finite approximations suggests it’s tracking something real about the underlying structure, even if individual measurements are necessarily finite.

This is like arguing “we only ever see one face of the moon, therefore the moon only has one face.” The limitation is in our perspective, not necessarily in the reality being observed.

Moreover, certain observations (like the flatness of the universe from CMB data) suggest physical infinity might be actual, not just theoretical. While this remains an open empirical question, it weakens the objection that “we never encounter infinity.”

Objection 3: “Maybe a Finite But Very Large Universe Looks Infinite to Us”

The Objection: “Perhaps the universe is finite but so large that our mathematics treats it as infinite for practical purposes. Infinity would then be just an approximation of ‘very big,’ not a fundamental truth. Why multiply entities by claiming actual infinity when ‘finite but huge’ would explain the observations?”

Response: This misses the philosophical point about the ground of being, though it raises a fair empirical question about physical cosmology.

The argument isn’t primarily about whether our particular universe has finite or infinite spatial extent—that’s an interesting empirical question, but not the core claim. The argument is about the nature of ultimate reality, the foundation that makes physics possible.

Even if our particular universe has finite spatial extent (which remains empirically open), this doesn’t affect the logical argument that the ground of being must be unlimited. A finite but very large universe would still need explanation for its specific size. Why 10⁹⁰ particles rather than 10⁹¹? Why this spatial extent rather than one meter larger? Why this configuration of physical laws rather than slightly different ones?

These “why this rather than that” questions persist until we reach something genuinely unlimited. A “very large finite” universe is still contingent—it could have been larger, smaller, or configured differently. It’s still a specific “brute fact” that needs explanation.

Moreover, applying Occam’s razor carefully: if reality is fundamentally finite but happens to be perfectly described by infinite mathematics across every domain we investigate, this multiplies mysteries rather than resolving them. Why would finite reality require infinite mathematics? The simpler explanation—that the mathematics reflects infinite structure—requires fewer unexplained coincidences.

The “finite but large” hypothesis doesn’t solve the explanatory problem—it just relocates it.

Objection 4: “This Is a Leap from ‘We Use Infinite Math’ to ‘Reality Is Infinite’”

The Objection: “Even granting that infinite mathematics works well, inferring ontology from mathematics is philosophically dubious. The history of science is full of useful mathematical tools that don’t correspond to anything real. Maybe infinite math is just our best current tool, not a window into reality’s structure.”

Response: This is the most philosophically sophisticated objection, and we acknowledge its force. Inferring ontology from mathematics is indeed problematic—which is why we’ve been careful about the inferential steps.

The response has three parts:

First, recognize the difference in scope. If one physical theory used infinite mathematics, skepticism would be entirely warranted. If a few theories did, we might still remain agnostic. But when quantum mechanics, field theory, thermodynamics, signal processing, and cosmology all require infinite structures—and all fail fundamentally when we try finite versions—the pattern demands explanation.

The systematic ubiquity distinguishes this from cases of historically useful but ultimately abandoned mathematical tools. Epicycles worked for planetary prediction but were replaced when we understood elliptical orbits. But infinity hasn’t been replaced—it has persisted and deepened through theoretical revisions from classical physics through quantum mechanics to quantum field theory.

Second, the direction matters. We’re not imposing infinite mathematics onto reality and finding it works—we’re discovering that reality forces infinite mathematics upon us when we try to describe it accurately. The mathematics emerges from trying to capture the phenomena, not the reverse.

Fourier didn’t decide “I want to use infinity” and then make it fit. He found that understanding heat flow required infinite series. Hilbert didn’t impose infinite-dimensional spaces on physics—quantum mechanics turned out to need them. The pattern is discovery, not construction.

Third, inference to the best explanation. The alternative hypothesis—that reality is secretly finite but happens to be perfectly describable only by infinite mathematics across all fundamental domains—is far less parsimonious. It requires believing in a systematic cosmic coincidence: finite reality perfectly masquerading as infinite across every theory that works.

When one hypothesis (infinite structure) explains all the data (mathematical necessity across domains) more simply than alternatives (massive coincidence, unexplained anthropic selection), we should provisionally accept it. This isn’t certainty, but it’s rational belief based on cumulative evidence.

However, we grant: this remains inference to best explanation, not deductive proof. The gap between mathematical necessity and ontological commitment is real. We’re claiming the inference is strong enough to warrant serious consideration, not that it’s logically airtight.

Objection 5: “Infinity Leads to Paradoxes Like Zeno’s—How Can It Be Real?”

The Objection: “Ancient paradoxes about infinity (like Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the tortoise) show that infinity creates logical contradictions. If you need to cross infinite half-distances to reach a destination, you could never arrive. If infinity were real, these paradoxes would be unsolvable. Their persistence shows infinity is incoherent.”

Response: Resolved paradoxes demonstrate infinity’s coherence, not its incoherence.

Zeno’s paradoxes emerged from limitations in ancient Greek mathematics—from the absence of adequate tools to handle infinite divisibility and infinite series rigorously. Ancient mathematicians lacked concepts like limits, convergence, and real analysis that modern mathematics provides.

Modern calculus and set theory resolve these paradoxes completely:

Infinite series can sum to finite values (the sum of 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + … = 1)

Continuous motion is compatible with infinite divisibility

Limits give rigorous meaning to approaching a value through infinite steps

These aren’t workarounds or philosophical evasions—they’re genuine solutions showing the paradoxes arose from inadequate conceptual frameworks, not from infinity being incoherent.

The fact that we solved these paradoxes through better mathematical understanding of infinity actually supports the coherence of infinite concepts. If infinity were genuinely incoherent, no mathematical refinement could resolve the paradoxes—they’d remain contradictions no matter how sophisticated our tools became.

The historical arc is instructive: as our mathematical understanding deepened, apparent contradictions dissolved. This suggests the problem was in our concepts, not in infinity itself.